The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

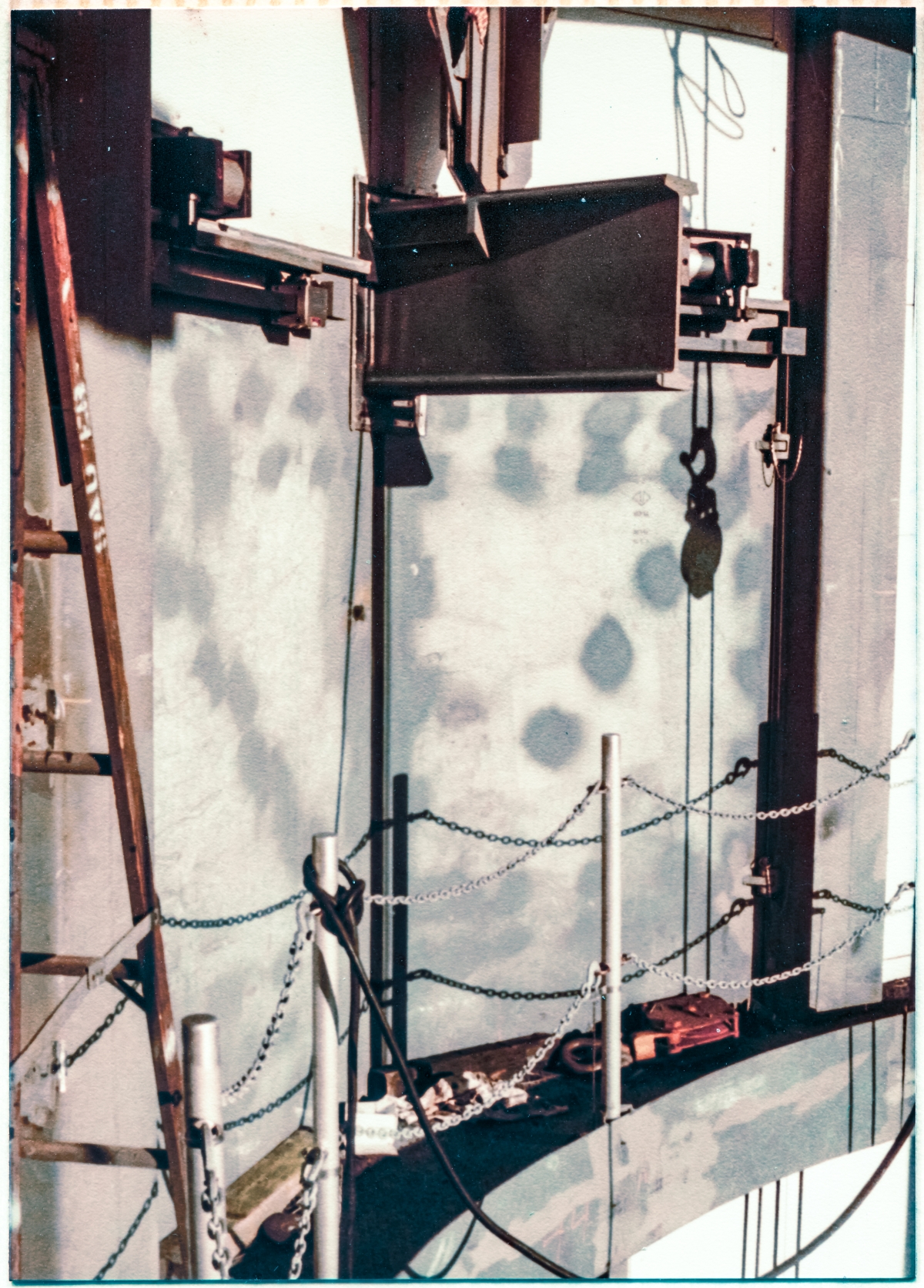

Page 31: Monorail Transfer Doors.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

Quick and dirty summary:

We're still right here on the Antenna Access Platform. Still right here on the ledge, at elevation 198'-7½", just under the RCS Room floor. And we're looking at the Monorail Transfer Doors, with the end of the Monorail that protruded out through the closed Doors, beyond the envelope of the Payload Changeout Room which is where the main length of that Monorail was located.

There's a story with this thing, and basically it was a whole lot of trouble and effort to fabricate and install this stuff, all jammed up underneath here, just beneath the RSS Top Truss, with a pair of heavy doors that opened inward and had an unpleasantly weird fit, and after we'd gotten it all in there, nice and pretty, full functional test and all, they decided they didn't want the damn thing anymore, had us weld those doors shut, and that was that. Ah well.

We shall revisit this madness in Part 2 of these stories, but not right now. There's too much other stuff to be dealing with, right now.

And by the way, as you're shinnying along against the unyielding steel of those doors, with the loose floppy handrail safety chains brushing against you on the other side, it's an unimpeded sheer drop of about 150 feet, all the way down to the concrete of the Pad Deck. So you don't really want to be spending too much time looking down as you work your way along this too-narrow bit of platform decking, and if there's a bunch of junk scattered along the ledge, a bunch of stuff you find yourself having to work your way around, in an area where there is no "around," stuff that would be oh-so-easy to stumble over, or maybe get tangled up with, well then, that just adds to the fun, now doesn't it?

The first time I ever set foot on a float was at this exact place here, where you see a removable handrail post with a red snatch block laying on the checkerplate ledge beyond it, which is where I had to go over the side and down about six feet of wooden ladder which was lashed on its upper end to this ledge of a "platform," which I had to depart, with the bottom end of the ladder resting on the float, resting on a four-foot-square piece of plywood having plain two-by-two's screwed to it around its perimeter to strengthen it up a little, dangling in suspension down there, held up by nothing more than some frighteningly-common rope attached at its corners, down beneath the too-narrow platform ledge you're seeing in this picture. The whole rig, ladder, float, and all, swayed and twisted alarmingly when you touched it, and swayed and twisted even more alarmingly when you entrusted your very life to it and you put your full weight on it. But I went, and I did, and I survived, so I guess it's ok, right?

Survive, I may have, but forget, I will not.

This is yet another area, and another example, of just how supportive Wilhoit's crew of Union Ironworkers was, when dealing with a new guy.

A scared guy.

A profoundly-frightened guy.

I've already described the unpleasantness of this ledge of a platform on the previous page, and the unpleasantness was stepped up that day, because of course, in order to get to the ladder that led to the float, and get down there and give things a look, up underneath the ledge at the top of the Payload Changeout Room Doors, the removable handrail posts and safety chains had already been taken down to provide Wilhoit's Union Ironworkers access to the ladder and float, and there was nothing along the perimeter of that horrifyingly-narrow ledge which might stop, or perhaps maybe even, just slow down a little, any toppling over the side that might occur as you were attempting to get yourself turned around in a place where there wasn't nearly enough room to do so, and take your first step backwards, out, down, and on to the upper ladder rungs.

And Dick Walls was still gingerly testing his new guy, seeing where his limits might be, and I know full-well that he had warned Red Milliken and whoever else (alas, I cannot remember) was in that gang of ironworkers that fateful day to watch me closely, and as I was being led out across the ledge, to the ladder, much as a condemned man might be led to the gallows, I could see them in my peripheral vision.

And I was taken to the ladder, and they were just about equal parts bemusement and dead-silent tack-sharp watchfulness, as they felt through me, what each of them had one day in the past, as a first-timer, felt for themselves, the fear of death, and how that person with the fear of death upon them was going to react to it.

And if you can do the job, then, you do the job, and there's nothing more to it than that.

And if it turns out that you can't, then that too is not only perfectly fine, it is to be encouraged, and no shame adheres to it, because you are being honest about it, and you are being honest with yourself and you are being honest with the gang of ironworkers who you have been thrown in with, up on high steel.

It's not for everyone.

And they will never fault you your inability to go where they go when you enter their world.

Nobody wants to deal with someone who has become paralyzed, or half-crazed, with fear.

But you must always feel the fear, lest you become reckless in your actions and your carelessness becomes an issue for those around you, and they find themselves then having to deal with you from the other side of things.

No. That is much worse, and everyone knows it.

Better to go as far as you can, realize you can go no farther, and then, with lucid judgment, go back.

It is better for everyone involved, and you are to be commended for your judgment.

And for myself, all of this and more was swirling around in my mind with senses heightened to a level that cannot properly be described, in a world that had become extraordinarily vivid, and extraordinarily sharp, and I went over the edge and down the ladder, feeling the vividness of its sway and the vividness of its repositioning itself with ropes creaking on every footfall on every next descending rung, hands tightly (but not too tight) gripping it, until the next footfall found itself on a mobile, piece of plywood, four foot square, plain and flat, wide-open all around with nothing whatsoever to impede motion over the side, suspended on ropes stretched taut at each corner, and it moved, and I moved with it, balancing, and still holding the ladder with one hand, I folded myself down into a sitting position on the float there next to the ladder, sitting there beneath the ledge on a flimsy wooden thing so small that you were right on the edge of it, all around, a skyscraper's distance into the air, just out of reach of the cliff face of the Payload Changeout Room Doors, right on the edge even when you were in the center of it, with the Pad Deck oh so very very far below, and the wilderness around, and the distant ocean beyond, all tack sharp in the outer reaches of my field of vision, and I swayed with the float as I sat with its edges all around me, and I extracted the notepad from my waistband behind me, and took my pencil, and then got to work, and drew the look of things up under that ledge at the top of the PCR Doors, and scribbled a few words and numbers that Dick Walls needed, and...

...nothing more than that.

Finish.

Get out of the way.

Come up out of a folded sitting position with the edge close crowding in on you, all around.

Back up the sickeningly-swaying ladder to the sounds of creaking ropes.

Back across that fearful ledge, no handrails, no safety chains, cold steel brushing against my right shoulder, pushing me toward the terrorizingly-open void on my left.

Get out of there.

Union Ironworkers have work to do.

But.

Until I was completely out of there, the bemusement and the dead-silent tack-sharp watchfulness remained.

On their faces.

In their eyes.

Until I was gone.

And people ask me, "What was it like?"

And I try to tell them.

I try to tell them what it was like.

But I do not know if I'm succeeding or not.

And of course, now I find that I've come to the hard part of telling The Tale of the Monorail Transfer Doors.

And the hard part consists in trying to figure out how much of this stuff, the stuff in the photograph at the top of this page, do you actually want to know about.

And half of my brain is telling me, "Let it go, man. Nobody wants to know all this ridiculously-arcane structural-technical-political crap."

And the other half of my brain is telling me, "There's going to be few. There's going to be a very few, who will want to know."

And if I do not put this here...

...who will?

I am all alone in a vast desert of information...

...and there is no one else.

I have looked.

I have looked long and hard.

And I am all alone out here, and I must do for myself or it will not be done at all.

Ever.

And there will be those travelers who come this way after I'm gone and they will find nothing, not so much as a few scattered bones, bleached white beneath this unforgiving desert sun.

And me, being me, I think I'm going to put it all down, and let those who want to travel through it all, and see it all, do so, and let those who want nothing whatsoever to do with any of it, skip down, skip across, skip to the next page, skip the whole damn thing, skip whatever.

So ok.

So I guess I just made a decision, here and now.

So here we go.

Wish me luck.

In the beginning...

There were the Monorail Transfer Doors.

And I was the New Guy, and I worked for Sheffield Steel, and Sheffield Steel fabricated the Monorail Transfer Doors, and all of the rest of the Curtain Wall of which they were a part of, including the Antenna Access Platform at elevation 198'-7½", and as the New Guy, I had no idea what any of it meant, what any of it did, or why any of it might be what it was, the way it was, and the depth of my ignorance was beyond fathoming, and it didn't mean a damn thing anyway, because Wilhoit's Union Ironworkers were tasked with hanging the iron, and so long as the iron got hung, who cares?

And I would suppose that a normal person would content themselves with things as they were, and let it go at that.

But not me.

Noooo.... not James MacLaren.

James was deeply irritated at not knowing, and set out to find out, and unknowingly set himself a forty-year task, in so doing.

Whoa!

Had I known what I was getting myself into....

....pshit. I would have done it anyway.

That's just how I am, I guess.

And not long into my newness at the Pad, Wilhoit got to the part of things where the Monorail Transfer Doors needed to be hung on the tower, and things on the drawings did not quite match things in the real world, and by this time Dick Walls had gotten into the habit of sending his James MacLaren up on the tower with paper and pencil to render that which was wrong (Remember back in the beginning of this thing, when I told you I was going to be telling you the full story, including the parts about the people in the story? Well guess what? I was one of those people too, and for that reason, I turn out to be part of the story, too.), with a sketch of sorts, and particular dimensions of particular things, taken with a tape-measure when and if possible, or perhaps simply being held by the hand by one of Wilhoit's ironworkers who would lead me to the thing in question and describe the wrongness of that thing in his own native tongue, and then I would return back down to the field trailer with my sheets of paper which told a tale of whatever it was that was found at the time, and try to further Sheffield Steel's interests in so doing.

And James MacLaren became involved, with the Monorail Transfer Doors.

And the Monorail Transfer Doors were complicated.

And they were tricky to build, and they gave the people down on Sheffield's shop floor no end of trouble because drawings that looked good, were in fact, not good.

The Monorail Transfer Doors were doors, after all, and as anyone who's done door work can tell you, doors (and windows too, for that matter), are different, and the differences come in the greatly-reduced level of tolerances. Tolerances for any mis-fit. Tolerances that become quite tight and unforgiving of very small deviations from precisely plumb, square, and true. Deviations that will never make themselves apparent to the human eye. It's not until you start in on trying to fit the damn thing, that you suddenly realize that your frame, the thing in which your door fits, is not exactly plumb, square, or true. And the door (which will also not be perfectly plumb, square, and true, either), then refuses to work properly. Or at all. It won't open. Or it won't close. Or a corner of it hangs while the rest of it tries to move, and cannot. And you address the offending corner, only to discover that now things are hung, somewhere else. And things you never ordinarily think about start entering into your troubles. Things like the different rates of expansion and contraction of the door, and its skin panels, and its frame, as the sun comes up in the morning, and shines directly onto your door after a chilly night, heating it up, even as the more massive, and much-more heat-conductive structural framing steel around it remains at essentially the same temperature, and you discover to your horror that the goddamned door will refuse to open and close, but only between the hours of nine and eleven A.M., and only on cloudless days, then. And other things. And worse things. Too.

Doors are a huge pain in the ass, and nobody has the least idea about any of it because nobody actually has to hang their own doors.

It's specialty work, and you get a specialist to do it if you want it done right.

The Monorail Transfer Doors (Nobody ever used an acronym for them. Nobody ever referred to them as the MTD. They were always the Monorail Transfer Doors, and I shall never know why that was, it just was.) were complicated-enough, and possessed of enough idiosyncrasies and peculiarities that they were very troublesome even for people who had been doing this sort of work all their lives, people working with drawings, people working with tools, and in fact everybody.

And of course, this being a Launch Pad, after all, there entered into considerations many other things that you would never think to consider when hanging a door.

We had no end of fun with the actuators for the Monorail Transfer Doors.

Look closely at the drawing that calls them out.

Now look closer.

And just you tell me, how the hell does this thing go together?

There are no sensibly-usable dimensions or information for the actuator, or where it goes, or how it gets there, or how it stays there.

NONE!

And it fact, we have no way of knowing if the actuator will even fit in there as-shown in the first place!

Whoever it was that made this drawing, and whoever it was that checked and approved this drawing, were both (and I'm sure they had company, too), just whistling past the graveyard with this one.

They just grabbed it out of a catalogue somewhere, pasted it in there, and hoped nobody would notice and further hoped that it would somehow fit, as-shown.

And as it turned out, it didn't fit!

And not only did it not fit, it turned out that there wasn't even any way to attach it. At all. Nothing.

And those who whistled past the graveyard were found out, in the air, by Wilhoit's ironworkers.

With a clock running.

And real money flowing.

Down a hole.

And as for Sheffield's new guy?

The Village Idiot had no prayer with these things.

But that didn't keep him from trying, either.

And somewhere in the middle of all that, the new guy was sent, by The Fates, once again, up to the Dreaded Antenna Access Platform, and came back down with this.

And this is a devious thing indeed for people who are not machinists or mechanics or ironworkers, and is not an easy thing to make any kind of sense out of, nevermind good sense.

And no, the new guy did not come up with the solution to the problem that is shown on the sketch.

The new guy was spoon-fed this solution by a grizzled old ironworker who knew how things worked, and the new guy faithfully produced this detail down in the Sheffield Steel field trailer as an ongoing part of the larger set of depictions which included those which were scribbled on the sheet of paper he brought back down off the tower, down from high steel, unquestioning, unknowing, putting well-placed trust, once again, in Wilhoit's ironworkers, and in so doing, by small steps and large stutters, learning for himself, how things were done. Up on high steel.

Now look again at the contract drawing, and then look at the fix, and now tell me how to get from one to the other, adhering strictly to the contract (which you did, or suffer dire consequences if you didn't) to do so.

No.

Not gonna happen.

And this set of issues with the actuators was multifarious, and at each new stumble along the way, following the resolution of the last problem and then having to deal with the next problem, one problem at a time, submitted in writing, in sequence, untouchable until an approved reply was handed back down from above, from the NASA side of the house, because there was no other way to do it; certain parties became difficult.

Certain parties in positions of authority began to get attitudinal.

And the new guy learned about Great Projects, and he also learned about Small People.

And with Small People, there exists a strong desire to hand-wave, and to become dismissive, and to try and belittle you, and intimidate you, and you learn to look for these signs, because these are the signs of someone who does not know.

And when a Small Person does not know, the last thing in the world that Small Person wants...

...is to know.

What they want, is to lord it over. To behave dictatorially. Imperiously.

And in so doing, cow you down.

To keep you from learning they do not know. That they are incompetent.

And so you learn to look for the signs, and keep a careful book on them, and bide your time, and feed them as much rope as they ever might want while you do so.

And in the end, as it always must, the rope you gave them is the rope they hang themselves on.

By the book.

By your book.

And in the middle of all that, slowly accumulating, questions.

What is this stuff?

Nobody knew.

What's this stuff do?

No answer.

Why? Why is is this stuff here?

Silence.

And it grated on me.

And the louder the silence grew, the less I liked it.

And the work went on, by fits and starts, and finally it was done, and we gave the whole system, a functional test, per the contract, doors, actuators, hinges, hardware, and all, and it all worked exactly as it was supposed to. It all worked perfectly.

And my questions continued to accumulate.

If those are the Monorail Transfer Doors, well then, what's getting transferred?

Nobody had the faintest idea.

And if something's getting transferred, what's doing the transferring?

It's a monorail, right?

And everywhere else on this tower, wherever there's a monorail, there's a hoist that hangs underneath it, and this particular monorail, up here in the far upper reaches of the PCR, and extending outside of the PCR a little bit, is by far the heaviest piece of monorail steel on the whole tower.

Which, in a world that makes sense, would seem to dictate one hell of a big hoist hanging up underneath it.

Where's the hoist?

Dead silence.

Why is this thing sticking just a wee little bit out past the envelope of the PCR up here and why does it need its own set of doors.

Nothing.

From anywhere.

From anybody.

And then, it was as if the gods themselves decided to step up their game a little, and subsequent to the completed functional test, we received, with NO explanation, a directive to remove the actuators and weld the doors shut!

Full seal weld across the curved gap in the Antenna Access Platform checkerplate where the door leaves faced each other, and the straight gaps where they faced the adjoining fixed platform decking on either side of them. The whole thing.

No more doors.

With no explanation, and nobody that I ever crossed paths with ever had the faintest idea... why?

WHY?

And for forty years no answer was ever given to me.

Until I started doing these essays, and I got to the part where the photograph at the top of the page is, and I started digging.

And that photograph up there...

...was specifically taken because of the Mystery of the Monorail Transfer Doors.

Which mystery had already taken deep root in my mind, even before we removed the actuators (which had yet to be removed and are plainly-visible in the photograph) and welded the doors shut for once and for all.

And the monorail itself...

Which, despite its having been rendered completely nonfunctional, was never removed, remaining in place for the full life of the RSS...

Was an even greater mystery.

What in all holy hell could this thing be for?

And forty years went by.

And over the course of that forty years, The Great Library of Alexandria was exhumed, in small bits at first, but increasing in speed and scope with the passage of each new year, until it had become much larger, much more ramified, and very much more robust than it ever was originally, and it was given a new name, and its new name was The Internet.

And I could not believe my good luck in having survived long enough to witness the full exhumation, nor could I believe my further good luck at being able to freely visit The Library, whenever I might want to, which turned out to be very often indeed, and I worked hard to hone my skills as a researcher, to distinguish proper fact from proper bullshit, and to learn the ways of reasoned inquiry.

There is much rubbish in The Library, and not all of it is easily-identifiable as rubbish, and one must be very very careful to avoid falling into the trap of being guided by unqualified people and institutions harboring malice, or greed, or narcissism, or delusion, or willful wrongheadedness, or any number of other unfortunate things in their hearts, or even some combination of them simultaneously.

But it's a doable task for the wary, for the sharp-eyed, for those who do not uncritically accept the well-intentioned words of friends, ill-intentioned words of foes, or the straight-up garbage that comes from fools, at face value, and instead seek to verify, to measure, to corroborate, to identify well-hidden agendas, prejudices, stupidity, and axes to grind.

The information is there, but it's work to prize it out from the dense rocky matrix of bullshit which it is oftentimes deeply-embedded within.

And as my digging into The Mystery of the Monorail continued, one day, in The Library, I came across this.

Which may, at first, appear only as yet another anonymous flake of snow falling from the sky during a particularly heavy blizzard, but if you read it, and if you examine it, you will discover that it holds the key to The Mystery of the Monorail.

And at long last, we have our answer.

Observe.

Four drawings, all on one page. Ok, fine. I'll separate them out for you, so you can see things a little better, ok? These images were taken from a very old .pdf, and whoever, or whatever, rendered the original material (which itself was very likely a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy...) was being looked over by someone who did not want to spend a single minute more on this task than the absolute bare minimum, so the poor schlub who did the work just kind of slapped it through, and we today, viewing their work from over forty years later, wish that their impatient, penurious, boss had been a bit more forgiving of his multi-decadal descendants, and put a little more time into things, but alas, it was not to be.

So I work with what I've got today, and I do the best I can by trying to clean it up some and make things more legible, and hopefully my multi-decadal descendants will look upon my efforts with a bit more charity.

Here's the first image, and here it is again, highlighted.

You're looking at an elevation view of the PCR part of the RSS, with RCS Room and Hoist Equipment Rooms on top of it, and slap up against the front of the PCR, is a Payload Canister in mated position. But it's not a normal Payload Canister. It's taller than a normal Canister. It goes all the way up to the underside of the RCS Room! And inside of it, up in the tallness up top, you can see a monorail hoist which is shown holding up an IUS, dangling on a line, down near the bottom of the Canister. Hmm.

Look close, and you'll see that our monorail hoist inside of the Canister is supported on a monorail beam which is inside the Canister, but seems to continue on past the edge of the Canister somehow. Hmm hmm.

And that monorail beam (which is labeled "Hoist Track" in the drawing) extends right out into the PCR, just beneath the roof, all the way back to the very far end of things to where it sits up there, up above a fully-retracted PGHM, which seems to have "staying out of the way" as its primary function in these drawings, which is kind of a funny way for PGHM's and Payloads to be working together, yes? Hmm hmm hmm.

Ok, now here's the second image, and here it is again, highlighted.

This image is more or less a reproduction of the first image, but in cutaway isometric view, to maybe help us along with understanding what it is that they're trying to show us here, and what they're showing us here is an IUS, inside of a Canister, suspended underneath a nice sturdy hoist, that itself is suspended underneath a nice sturdy monorail beam.

And now we get to our third image, and once again, here it is, highlighted.

And this one is another cutaway isometric view, and it's making things pretty clear that they're working this stuff through open doors in the bottom of the Canister, and the hoist line goes pretty much all the way down to the Pad Deck, where you can see a couple of eency teency Lego minifig-looking people on an eency teency Lego truck kind of thing, hanging around beneath a suspended lift (not recommended) which seems to be some sort of secret payload, hidden beneath a shroud.

And now we come to our fourth and final image, and here it is, highlighted.

Which is another cutaway isometric view, and seems to add little to our already-sufficient understanding of things, but they went ahead and changed the look of the secret payload for some reason or other, and they also decided to let us see that they were lifting who-knows-what-else, over on the back side of the RSS, using a different monorail hoist, about which we will learn many other strange and wonderful things when we get to the photograph that includes the monorail beam it hangs from, but not right now, ok?

And what actually winds up happening here is that they were going to make a Special Canister. Quite a bit taller than the one they actually wound up with for normal payload operations, and which also had inside of it, up in the very top, a substantial piece of iron which was intended to match our monorail beam exactly, and which perforce was going to have to butt up, flush against, the end of our monorail beam in the RSS, with sufficient strength, rigidity, and precision as to permit the pair of trolleys which support a monorail hoist which itself was carrying over thirty thousand pounds of live, fully-fueled IUS to roll back and forth across the discontinuity, and there's always going to be a discontinuity in the form of a gap, or maybe a ledge or a sort of step, and I don't care if it's only a half-millimeter, it's there, and between differential thermal expansion and contraction, flexures of the Special Canister caused by wind-loading and variable center of gravity loading induced by a mobile load, flexure of the RCS Room main framing steel along with the canister support boom pendants, and who-knows-what-else, there's going to be some kind of mismatch, no matter how small (you hope). And oh by the way, does this mean we're going to have to furnish and install a separate, special, shorter, set of boom pendants to accommodate the greater elevation of the lifting lugs they'll attach to, which will be on top of our Special Canister, and how are we going to go about the business of switching the pendants back and forth whenever we switch from our normal Canister to our Special Canister, and then back again, and you can bet your ass we're gonna have to figure out every last bit of that stuff, and lots more that I'm not even gonna bother you with right now with respect to the rest of the RSS/PCR structure, and who knows, maybe the phase of the moon too? That discontinuity is never going to be fully trustworthy, and now you've gotten yourself into a situation where the wheels on the monorail support trolley have decided to hang up on that discontinuity, which has become ever-so-slightly misaligned, but still plenty more mismatch than might be minimally required to interfere with the smooth travel of something that's being pulled down onto the upper surface of the lower flange of the monorail beamS by the tonnage of fully-fueled load its bearing, and how hard are you willing to bang on things to get that trolley wheel to jump the goddamned misalignment it's hung on, and you're playing around with thirty-thousand pounds of goddamned dynamite here, and what the hell were you people thinking when you came up with this thing, anyway?

So basically they wanted to be able to do some pretty heavy lifting without having to lift an entire Canister, at certain points along the way, but which heavy lifting would require the services of a Special Canister (So, apparently we are going to be having to lift a Canister anyway, hmm?), one having enhanced capabilities, in order to...

...and we never quite made it to the particulars of that "in order to" part, and things were left just sort of dangling there, without precise objective, without precise operational procedures, without precise purpose, and the monorail and the doors found their way into things, but nothing else did, and the Special Canister was never built, and in the end...

...nothing.

And all of this stuff stems from some dim Paleoshuttle Time before real things took actual shape in the real world, made from metal and worked by people, when clouds of desire floated aloft, viewed by persons on the ground far beneath them, along with Three Letter Agencies, Money Holders, Political Fixers, and many other strange and wonderful creatures and features of the long-ago Earth of that dim Ur-time before Pads were finished and Flights began.

And if you didn't read the originally-referenced document when you first encountered it, well then here it is again, and if you still don't want to wade through the whole thing, well then here's the key, all nice and highlighted-up for you, giving us the specific (but strangely-vague and uninformative at the same time) purpose for the "special canister," but really, you should read the whole thing because it is not only instructive in a strictly-technical sense, it is also instructive in a cultural sense insofar as how the as-yet-unbuilt Space Transportation System was originally being presented to people, and how people wanted so much to believe the original premises, that they brought themselves to do so, even though some of the underlying foundations of those premises were perhaps not as sturdy as they would need to be if any of this stuff was to actually work as they claimed it would, in the real world, the one-and-only real world we'll ever have, but now we're getting more than just a little off-track, and we'll leave that end of things alone for now.

And by the time that Sheffield's New Guy showed up, much had transpired, and the real world had been allowed into the discussion-rooms, and Things Were Noticed, and at some point, the Whole Affair was tossed to the curb, and, as is often the case when people and agencies are found out to be wrong, it was all done beneath a cloak of silence without a word of explanation to anybody, and an imperious hand-wave of dismissal to those who might dare ask questions.

And the New Guy was learning.

He had a long way to go, but he was learning.

And his archaeological work continued on, and continued to yield results, not least amongst which was that King Tut's Unopened Tomb known as 79K14110, which contains riches beyond imagining, included a rendering of the hoist. The long-lost thing itself, which was to do the transferring through the Monorail Transfer Doors.

How it was that the new guy never managed to lay eyes upon this drawing while he was out there, out on the Pad, can never be known.

It's part of the mechanical package, and the new guy worked for a structural outfit, so perhaps the answer lies somewhere in that bank of fog, but then again, perhaps not. Maybe it was sitting right there in plain sight the whole time and the new guy was just too stupid to notice it?

Who knows?

Not me, that's for sure.

But I've got my hands on the drawing now, and just take a look at that thing!

Whooooo.... quite the brute, this thing is.

They weren't kidding around with this thing.

Not at all.

But it never happened.

It never made the transition.

From lines on paper to cold hard steel.

And while we're here, let's go ahead and give you the S18x70 monorail, too. The "S" standing for "standard" as opposed to what we see almost everywhere else, which is a "W" that stands for "wide-flange", and once upon a time...

There is deeply fascinating history with this stuff. Great Civilizations risen and fallen with this stuff. Great Wars and profound shifts in largest-scale cultural identity won and lost with this stuff. Languages spoken or not spoken by great blocs of people with this stuff. In too many very real ways to count, iron, and the steel which can be made from iron, constitutes the teeth and bones of civilizations.

Structural steel is so common that people think it is something that's always been with us, but it's actually a late-comer, and its astoundingly ramified and braided pathway into and throughout our present-day lives traces the the much-more-recent end of a grand arc of Great Civilizations, going back in time all the way to at least the 4th millennium BC in Egypt (and likely-as-not earlier and elsewhere, too), where pieces of meteoric nickel-iron had been literally picked up off the ground or accidentally found within it, which pieces were held in sufficient regard as to ensure their careful preservation at the time, and subsequent discovery and study by archaeologists and historians of the modern epoch.

Returning to our "S" shape, we find that it can stand for either "Standard" or "American Standard", and that nomenclature itself is an outgrowth from a time prior to any such terms being introduced into the industry in wide-scale usage.

Have a look at Pencoyd Iron Works "Wrought Iron and Steel in Construction" published in 1891.

"Wide-flange" beams, "S-shape" beams, and all of the other stuff we're used to seeing in the construction of large steel-frame structures... do not even exist yet.

This is back when the very first steel-frame "skyscrapers" were pushing the envelope, and things in the ten-story-high range were still improbable miracles, and not-yet fully trusted by everyone, nevermind the elevators it took to reach the tops of them.

They were too tall.

A thing like that must fall.

But they did not fall, and instead, they began to grow taller and taller and taller, and that trend is still under way, and where its ultimate limits using structural steel might be found, we do not at this time know.

Here's another reference book from the time, Carnegie's "Pocket Companion", published in 1892.

If you'd asked somebody for an S18x70 back then they would have had no idea what you might have been talking about.

Wide flange?

"What's a wide flange?"

And in the first few pages of both these proto steel handbooks, we get to see excellent renderings of the shapes of the beams, and they're ALL "S" shapes, and S-shapes are distinctive in that the flanges of the beam get thinner as you move away from the web, and are therefore sloped, and back in those days that was what you got when you ordered structural steel. Additionally, S-shapes tend to be "tall" in aspect, with relatively narrow flange widths compared to the depth of their webs.

And in the beginning, this was your standard I-beam, and the resemblance to a capital letter 'I' is quite strong.

Note also (and in all the other similar publications that can be found from this time) that the individual shapes had no systematized industry-wide nomenclature, and instead were identified via "in-house" nomenclature peculiar to whatever firm it might have been that produced them. Both books have their own, different, nomenclatures.

Railroads came first, and steel was produced in truly gigantic quantities for the first time ever, creating rails for the railroads which were at the time shooting out continent-wide tendrils all over the place in an ever-expanding web of coal-fired commerce.

It was only later on when building construction started to move upward that structural shapes started coming into wider usage, above and beyond such steel bridges, boats, and other specialty items as were already being produced, but bridges and boats are a much less common thing than buildings, and it was the buildings that really kicked all of this into the high gear which we still find ourselves a part of.

Back then, rolling any beams at all, and wide-flange beams in particular, constituted a very-difficult demand on the technology of rolling mills, and despite their superior characteristics, large-scale production of standard beams was delayed as a result, and wide flange beams did not happen at all, until later, also as a result. The stuff was a bitch to make.

But it was a much better breed of cat, and steel producers stayed with it until they figured the process out.

Down at the bottom of page 509 in "The Making Shaping and Treating of Steel" by Carnegie Steel, 1920, we get a glimpse of that long-gone time when they were still working it out down on the factory floors.

And now we can see why wide flange beams are called "wide flange" beams.

They constitute a major improvement in steel shapes for construction, and they're significantly different-looking from what came before.

An awful lot of them are not 'I' beams anymore. They're 'H' shaped.

And finally, in the middle years of the 20th century, the business of steel production had settled in to a groove, and steel mills were churning out both different structural shapes, and somebody has got to get on top of this stuff, and gain control of it, or otherwise a very large industry indeed, in the absence of any systematized standards that can be generally agreed upon, is going to become too confusing and unwieldy for it to work efficiently, and so, by the time you get to Hot Rolled Carbon Steel Structural Shapes, published in 1946 (shortly after the greatest demonstration of the fearsome might of well-organized large-scale steel production and usage the world has ever seen), you can see that S-shapes are now specifically called out as such, to distinguish them (and, of course, their very different engineering peculiarities and particularities) from the other structural shapes, including wide-flanges.

And wide flange beams and columns completely took over from S-shapes, but not to the extinction of S-shapes, which continue to be produced, and they have their uses.

And, oddly enough, one of those uses takes advantage of the fact that an S-shape has much narrower flanges, which are sloped on their interior surfaces. Both characteristics, relative narrowness and slope, in combination, make them ideal for hanging monorail trolleys from beneath them. The countering slopes cause the trolley to self-center, precluding concerns about the wheels of an off-center trolley interfering against the web of the beam, and also keeping the trolley on-course in the same place at all times, and the narrowness permits the trolley wheels to be attached to a narrower-span support frame, and the narrower the span, the stronger the frame, and the cheaper and easier it becomes to manufacture.

So it's a perfect match, and everywhere on the tower you might find a monorail beam holding up a hoist, you're going to be finding yourself an S-shape.

So now you know. Now you know why, and it's important to know why. Knowledge is power, right? Just might keep you out of trouble one day. Who knows?

So our S18x70 monorail beam is just right, and it's also nice and strong.

Nice and sturdy.

The whole works, beam, supports, pins, allofit.

Very Sturdy Construction.

And I do not know precisely why but clearly, they wanted that monorail to be able to swing side-to-side. To pivot along its long axis from a point up above it just a little.

This is interesting stuff, and I'd love to know what drove the decision to hang this monorail from pins, giving it the ability to swing.

What swing?

Why swing?

No answer.

Sigh.

They saw themselves in here with a live Inertial Upper Stage, or perhaps an equally live payload, and not just any payload, but a military payload. Or perhaps an NSA payload. Or a CIA payload. Something special.

Something which demanded that the monorail, attached directly to the RSS Primary Framing, from which a heavy hoist hung in suspension, with its load hook suspended yet again, on wire ropes, needed to be able to rock back and forth, side-to-side, for some reason.

And I'm pretty sure we'll never know why in any kind of original documentation sense, but maybe (and this is strictly guesswork on my part, so be mindful of that, ok?) the pinned monorail inside the PCR matched up with a similarly-pinned monorail up in the top end of the Special Canister, and so long as the two steel members were aligned correctly in the horizontal plane, the pins would also force good alignment in the vertical plane, as freely-available gravity yanked them both downward, and kept them both in the one-and-only lowest possible position when a load was being applied to them, and... perhaps.

But again, it's just a guess, and no more than that, ok?

Whatever it was, it was quite-serious stuff.

You don't go building heavy-lift gear this way unless you've got a reason.

Ah well, so it must be.

And as a final note of unanswered curiosity, how would a thing like that, a thing purpose-designed to rock back and forth, work with a monorail poking out through a close-fit clean-room sealed cutout in a pair of closed doors?

Or was whatever it was that rocked, or perhaps only might rock the monorail from side-to-side, only supposed to come into play when the Monorail Transfer Doors were open? And how might a thing like that work? And I'm sure I'll never know.

\\\\\\\

ADDENDUM, 2023 02 10:

Our answer to the business of swing comes in the form of not swinging at all, but instead, as with the collaterally-beneficial characteristics of the sloped flanges on our S18, the whole thing hangs from pins to allow and ensure self-centering of the monorail as it carries its outrageously explosive and expensive burden, the better to ensure they won't lose it as they move it.

///////

And without otherwise being asked for, perhaps in exchange for not getting an answer to the question we just asked, the answer to a previous question (which we may have already figured out on our own, but perhaps not) snaps neatly into place.

And here's your answer, pretty as you please, on a drawing you've already seen, but you were too busy laughing at the horrid rendering of the technician with the loose wrench in his pocket to pay close-enough attention to the way monorails and ladders dance together a couple of hundred feet up in the air, and anyway that was before we had gotten all the way to the bottom of the monorail part of things in the first place, and were therefore less aware of such things, at the time. They wanted that monorail, and they got that monorail, and with the monorail in there, other stuff, stuff like our ladder, was forced to yield right-of-way to accommodate it, and that's how that works, ok?

And when you're up on the Antenna Access Platform, things just keep on coming at you, eh?

Let's go back to the photograph again, for something you can't see, and then I'll point out a few more odds and ends for you, ok?

And then maybe we can finally get the hell out of here.

There's something else that does not jump right out at you up in this area, and that would be the fact that this part of the curtain wall, the part which consists of just the Monorail Transfer Doors themselves, with their little ledge of a platform hanging off of their exterior sides down at the bottom, has even less structural integrity than the already-not-very-well-endowed structural integrity of the whole curtain wall area exclusive of the doors.

The whole thing, doors, platform ledge, and all, is being held up by nothing more than a pair of hinges, one pair per door, and nothing else.

If the hinges were, for some unknown reason, to let go, then the only other thing keeping this stuff up in the air would be the locking lugs with their detent pins, which of course never saw such loads as part of their day-to-day purpose of making sure the damn doors were never blown open, come launch, come hurricane, come what may, and you would hope that, as a fail-safe, they'd keep things more or less where they belonged.

And you'd be walking around up there and you'd be grumbling at the cramped confines, and staying watchful about going over the side, and your mind would just not hold on to the fact that this whole thing here, smack-dab in the middle of the Antenna Access Platform, was more or less hanging by a thread, and you were hanging right along with it, blissfully unaware.

But then the doors got closed one last time, for once and for all, and the checkerplate got seal-welded, and after that... it was better.

...but it was never good.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEContact Email Link |